Racial/ethnic disproportionality in child welfare has been a topic of interest and controversy among child welfare researchers and administrators since data became available that permitted its investigation.

These findings from a Casey study in 2007 [1] highlight the over- and under-representation of ethnic groups in foster care:

- Black children are overrepresented in foster care by a ratio of 2:1

- Native Americans are overrepresented in foster care by a ratio of 2:1

- Whites are underrepresented by a ratio of 0.7:1

- Hispanics are underrepresented by a ratio of 0.9:1

- Asians are underrepresented in foster care by a ratio of 0.25:1

Disproportionate Need or Discriminatory Practices

Citing Hill (2006) [2], Casey Family Programs states that three national incidence studies revealed no significant differences between the base maltreatment rates of Black and White families.

This lack of differences in base rates suggests that disproportionality in the child welfare system is not due to disproportionate need, but rather to discriminatory practices in society (reports of abuse and neglect) or within the child welfare system (investigations, substantiations, placements, permanency outcomes).

Addressing Disproportionality

In order to determine effective strategies for reducing disproportionality, I undertook a study to examine an effort to address disproportionality with a policy and practice initiative utilizing Intensive Family Preservation Services (IFPS). [3] The study was based on data from the state of North Carolina:

IFPS is available in 70 of the state’s 100 counties, although IFPS is not available in sufficient quantity in any county to respond to all eligible families.

- Families eligible for but that did not receive IFPS received traditional public and contract agency services, such as, counseling, skill training, protective supervision, day care, etc.

- The study employed a retrospective, population-based design that permitted the selection of all high-risk abuse and neglect cases.

- Data were merged from various statewide (NCCANDS, AFCARS) and program-specific (IFPS) databases.

- The study included 2,056 high-risk families that received IFPS, and the comparison group included 28,004 high-risk families.

- About three-fifths of the treatment population was White, a little more than one-third was Black, and the remainder comprised American Indians, Hispanics, and Asian/Southeast Asian families.

- There were no differences on placement rates between Blacks and non-Black minorities, so these groups were combined.

- White and non-White racial groups within the IFPS treatment condition were essentially equivalent with the exception of non-Whites having slightly more substantiated prior reports. Theoretically, any increased overall risk associated with this difference would be likely to diminish, rather than enhance the treatment outcome being investigated.

- Independent variables: race, risk, IFPS versus non-IFPS

- Dependent variable: cumulative risk of placement

The Results

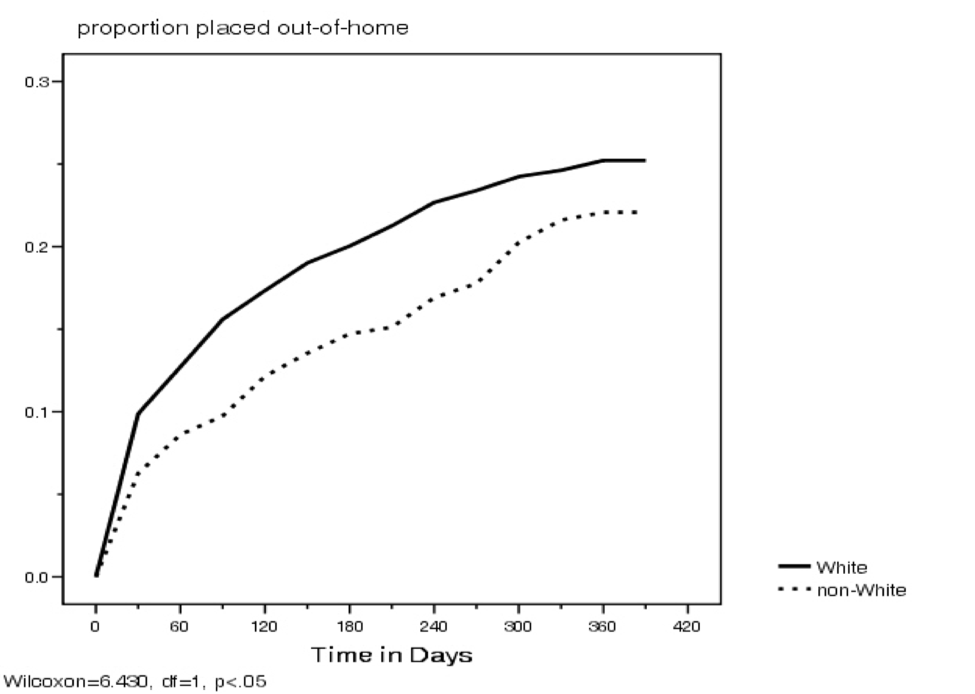

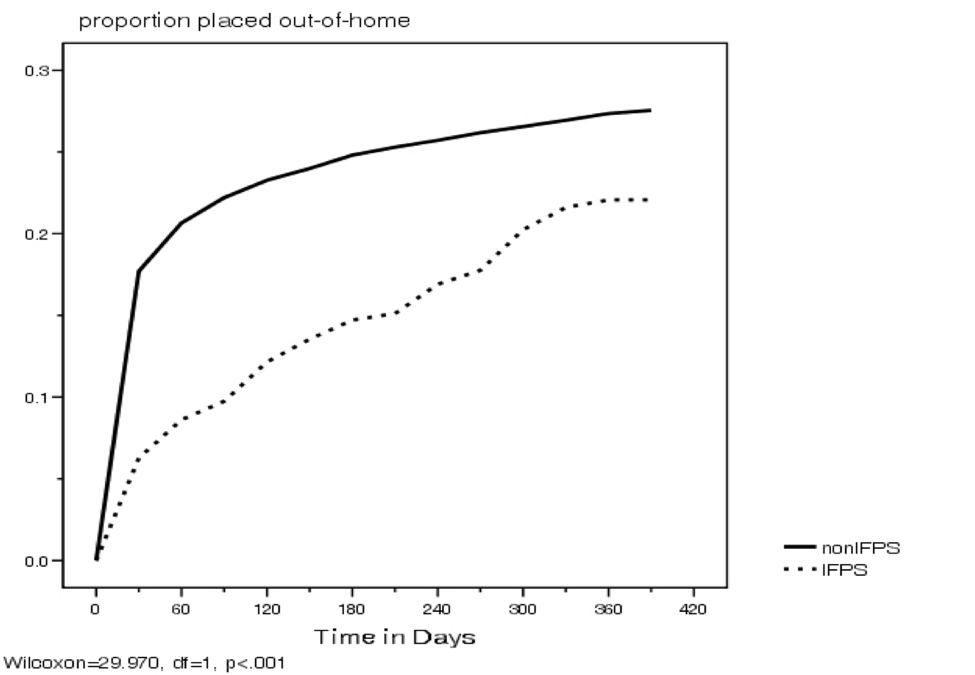

- High-risk minority children receiving traditional services were at higher risk of placement than White children, but minority children receiving IFPS were less likely to be placed than White children.

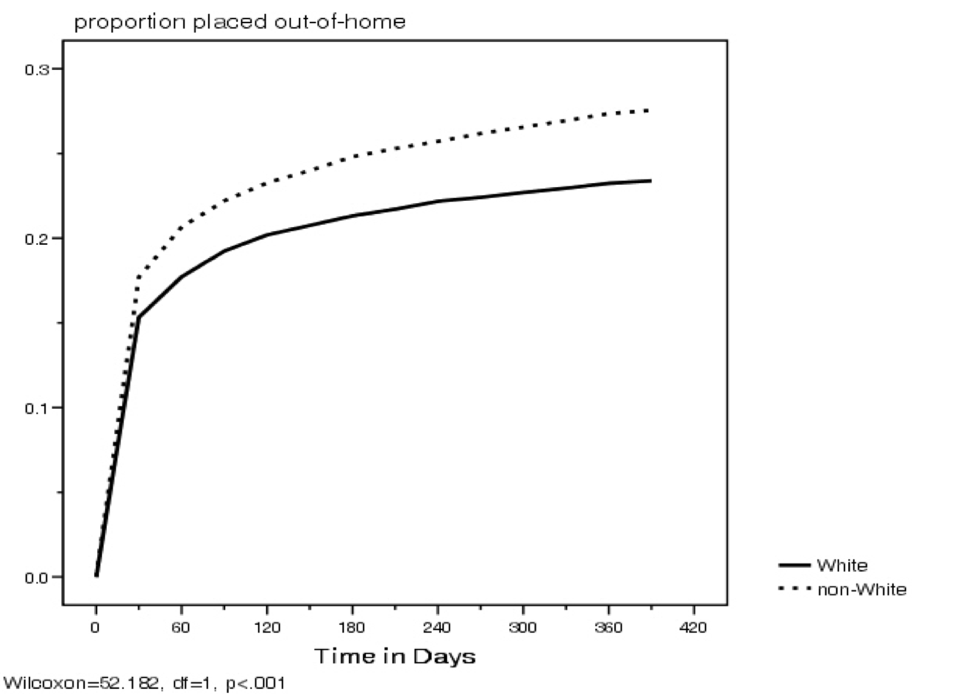

- When only minority children were examined, those receiving IFPS were less likely to be placed than those receiving traditional services.

Figure 1—Risk of Placement After CPS Report for Children Receiving Traditional CW Services by Race

Figure 2—Risk of Placement After Referral to IFPS for Children Receiving IFPS by Race

Figure 3—Risk of Placement After CPS Report/Referral to IFPS for Non-White Children

Conclusion

IFPS is associated with a reduction in racial disproportionality of out-of-home placement among high-risk families. Within-race analysis suggests that IFPS may mitigate racial disparity in out-of-home placement existing in the remainder of the child welfare population that receives traditional services.

References

1. Casey Family Programs. (2007). Fact Sheet: Disproportionality in the Child Welfare System: The Disproportionate Representation of Children of Color in Foster Care.

2. Hill, R.B. (2006). Synthesis of Research on Disproportionality in Child Welfare: An Update. Washington, DC: Casey/Center for the Study of Social Policy Alliance for Racial Equity.

3. Kirk, R.S. & Griffith, D.P. (2008). Impact of intensive family preservation services on disproportionality of out-of-home placement of children of color in one state’s child welfare system. Child Welfare, 87 (5), 87–105.

_______________

Posted by Ray Kirk, Researcher

Dr. Kirk’s research on the child welfare system includes assessment tools, IFPS, reunification, and prevention.