Two weeks ago, we looked at the IFPS new worker training offered in New Jersey. (See IFPS in a University Setting.) This week we look at the training provided in North Carolina. Both North Carolina and New Jersey offer six days of training:

North Carolina Training

Family-Centered Practice in Family Preservation Programs is a six-day specialized curriculum designed for family preservation and other home-based services workers, which provides instruction in the skills necessary for a successful in-home intervention.

Day One begins with an introduction to six principles of partnership that enhance a worker’s ability to provide family-centered services. Next is an overview of the training which follows the family preservation and reunification process through the Family Intervention Cycle. This includes seven stages of engaging families:

- Joining: screening and intake, relationship-building

- Discovery: assessment, reduction of resistance, setting goals

- The Change Process: treatment

- Celebration

- Closure

- Reflection: evaluation

- Follow-up.

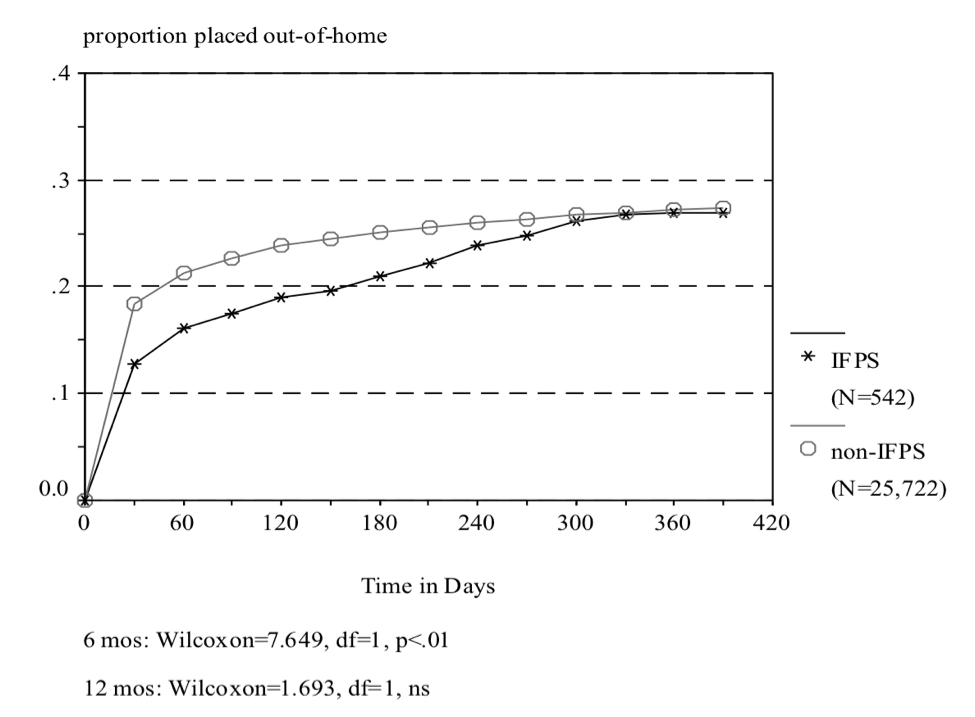

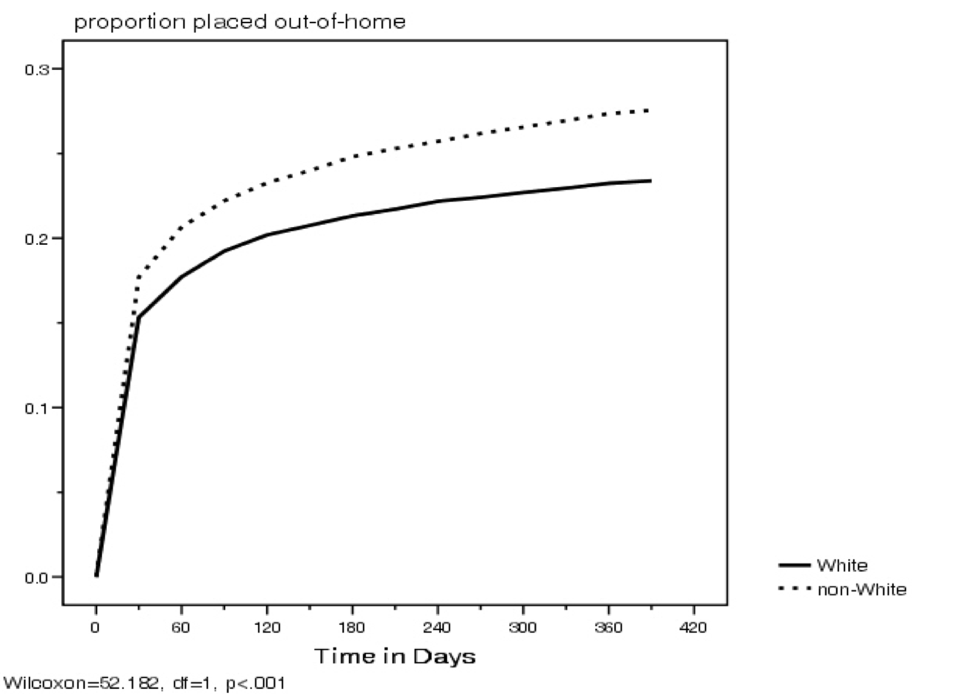

The IFPS model is introduced and its components are defined through reviews of policies and procedures, the history of IFPS in North Carolina, a video of IFPS in action, and outcome data. The role of cultural competency in IFPS is examined, and the day ends with participants practicing with case studies to determine whether or not they meet IFPS, FPS, or RS standards.

Day Two is spent examining the Joining Process, which includes developing relationships and how to get started with a family. The introduction of a “toolbox” on this day offers participants a visual tracking of skills, techniques or tools that will be presented throughout the training. The day ends with an introduction to two “practice” families which the group will track throughout the remainder of the training. One case study focuses on an IFPS/FPS and the other tracks an RS family.

Day Three provides an opportunity for each participant to begin to practice tools and concepts presented in the curriculum by applying them to the two case study families. This day focuses on the Discovery Process, and participants are asked to practice looking for assessment information through the use of video clips of the family. Multiple tools for discovery are presented and practiced.

Day Four begins with an examination of how family strengths can be used in the intervention process. Next, participants are presented with multiple tools for setting goals with families, then role play goal-setting with the two case study families. Record keeping is introduced and is tracked throughout by the use of sample client files for the two practice families. The Change Process is introduced on this day and the first two of five strategies for helping families change are reviewed: Changing Behavior and Improving Parenting Skills. The rest of the day is spent looking at behavior management and improving parenting skills. Throughout the day, participants are introduced to new tools and are given opportunities to practice them with the case study families.

Day Five continues with the Change Process by focusing on the remaining three strategies for helping families change: Examining Family Dynamics, Enhancing Communication, and Connecting with Resources. Practice opportunities continue throughout the day as the “toolbox” continues to grow.

Day Six begins with Celebrating Change which focuses on helping families improve during the intervention and move on after case closure. The curriculum focuses on evaluating the family plan, looking at ethical and safety issues related to IFPS/FPS/RS, writing crisis intervention and safety plans, and examining case closure procedures as well as follow-up requirements. The day ends with looking at options for transitioning families to follow-up care and connecting them with resources.

_______________

Posted by Priscilla Martens, Executive Director, National Family Preservation Network